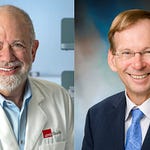

This week on Mendelspod, we speak with Petter Brodin, Professor of Pediatric Immunology at the Karolinska Institutet and Director of Systems Immunology at Imperial College London, about his pioneering work in childhood immune development and his new spatial-proteomics investigations into lupus.

Petter shares how a single lecture on natural killer cells pulled him into immunology, and how early twin studies convinced him that “our immune systems are shaped predominantly by non-heritable factors.” That insight drove him to study the earliest stages of immune development—when newborns leave a sterile environment for a microbial world that imprints their immune trajectories for life.

A major theme of the conversation is Petter’s insistence that immune responses cannot be understood by looking at cells one by one. As he puts it: “Cells don’t ever work in isolation, but historically we’ve always been studying them in isolation—and I think that’s fundamentally problematic.”

This systems view is now being partly enabled by Pixelgen’s spatial interactomics. Using their Proximity Network Assay, Petter’s group is finding that lupus B cells don’t just differ in protein expression—they differ in protein distribution, revealing organization patterns that classical flow cytometry cannot capture.

These spatial signatures may point directly to new, more precise therapies. Petter explains: “If there is a difference in protein–protein interaction or protein distribution that characterizes disease, then surely that indicates a dysregulation—and that is something we can target.” Instead of broad immunosuppression or depleting whole cell populations, future treatments could focus on the exact cell states driving autoimmunity.

Petter ends on an optimistic note: spatial interactomics won’t just help treat autoimmune disease—it may allow us to intervene earlier, even preventatively, as we learn how early-life immune disturbances set the stage for disease decades later.